What Is a Cell?

Trees in a forest, fish in a river, horseflies on a farm, lemurs in the jungle, reeds in a pond, worms in the soil — all these plants and animals are made of the building blocks we call cells. Like these examples, many living things consist of vast numbers of cells working in concert with one another. Other forms of life, however, are made of only a single cell, such as the many species of bacteria and protozoa. Cells, whether living on their own or as part of a multicellular organism, are usually too small to be seen without a light microscope.

Cells share many common features, yet they can look wildly different. In fact, cells have adapted over billions of years to a wide array of environments and functional roles. Nerve cells, for example, have long, thin extensions that can reach for meters and serve to transmit signals rapidly. Closely fitting, brick-shaped plant cells have a rigid outer layer that helps provide the structural support that trees and other plants require. Long, tapered muscle cells have an intrinsic stretchiness that allows them to change length within contracting and relaxing biceps.

Still, as different as these cells are, they all rely on the same basic strategies to keep the outside out, allow necessary substances in and permit others to leave, maintain their health, and replicate themselves. In fact, these traits are precisely what make a cell a cell.

What Defines a Cell?

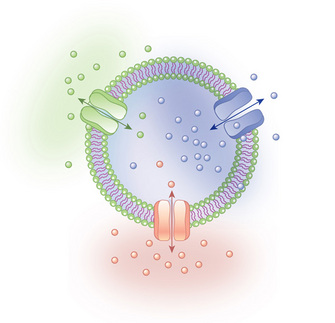

the center of it. Small beads representing molecules are hovering near the proteins, showing higher concentration either outside of the membrane or inside of it. The transport proteins are therefore regulating concentrations of molecules inside the cell, by controlling the passage of molecules through pores." />

the center of it. Small beads representing molecules are hovering near the proteins, showing higher concentration either outside of the membrane or inside of it. The transport proteins are therefore regulating concentrations of molecules inside the cell, by controlling the passage of molecules through pores." />

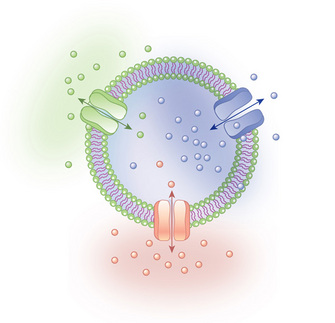

Figure 1: Transport proteins in the cell membrane

A plasma membrane is permeable to specific molecules that a cell needs. Transport proteins in the cell membrane allow for selective passage of specific molecules from the external environment. Each transport protein is specific to a certian molecule (indicated by matching colors).

© 2010 Nature Education All rights reserved.

Cells are considered the basic units of life in part because they come in discrete and easily recognizable packages. That's because all cells are surrounded by a structure called the cell membrane — which, much like the walls of a house, serves as a clear boundary between the cell's internal and external environments. The cell membrane is sometimes also referred to as the plasma membrane.

Cell membranes are based on a framework of fat-based molecules called phospholipids, which physically prevent water-loving, or hydrophilic, substances from entering or escaping the cell. These membranes are also studded with proteins that serve various functions. Some of these proteins act as gatekeepers, determining what substances can and cannot cross the membrane. Others function as markers, identifying the cell as part of the same organism or as foreign. Still others work like fasteners, binding cells together so they can function as a unit. Yet other membrane proteins serve as communicators, sending and receiving signals from neighboring cells and the environment — whether friendly or alarming (Figure 1).

Within this membrane, a cell's interior environment is water based. Called cytoplasm, this liquid environment is packed full of cellular machinery and structural elements. In fact, the concentrations of proteins inside a cell far outnumber those on the outside — whether the outside is ocean water (as in the case of a single-celled alga) or blood serum (as in the case of a red blood cell). Although cell membranes form natural barriers in watery environments, a cell must nonetheless expend quite a bit of energy to maintain the high concentrations of intracellular constituents necessary for its survival. Indeed, cells may use as much as 30 percent of their energy just to maintain the composition of their cytoplasm.

What Other Components Do Cells Have?

As previously mentioned, a cell's cytoplasm is home to numerous functional and structural elements. These elements exist in the form of molecules and organelles — picture them as the tools, appliances, and inner rooms of the cell. Major classes of intracellular organic molecules include nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, all of which are essential to the cell's functions.

Nucleic acids are the molecules that contain and help express a cell's genetic code. There are two major classes of nucleic acids: deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). DNA is the molecule that contains all of the information required to build and maintain the cell; RNA has several roles associated with expression of the information stored in DNA. Of course, nucleic acids alone aren't responsible for the preservation and expression of genetic material: Cells also use proteins to help replicate the genome and accomplish the profound structural changes that underlie cell division.

Proteins are a second type of intracellular organic molecule. These substances are made from chains of smaller molecules called amino acids, and they serve a variety of functions in the cell, both catalytic and structural. For example, proteins called enzymes convert cellular molecules (whether proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, or nucleic acids) into other forms that might help a cell meet its energy needs, build support structures, or pump out wastes.

Carbohydrates, the starches and sugars in cells, are another important type of organic molecule. Simple carbohydrates are used for the cell's immediate energy demands, whereas complex carbohydrates serve as intracellular energy stores. Complex carbohydrates are also found on a cell's surface, where they play a crucial role in cell recognition.

Finally, lipids or fat molecules are components of cell membranes — both the plasma membrane and various intracellular membranes. They are also involved in energy storage, as well as relaying signals within cells and from the bloodstream to a cell's interior (Figure 2).

Some cells also feature orderly arrangements of molecules called organelles. Similar to the rooms in a house, these structures are partitioned off from the rest of a cell's interior by their own intracellular membrane. Organelles contain highly technical equipment required for specific jobs within the cell. One example is the mitochondrion — commonly known as the cell's "power plant" — which is the organelle that holds and maintains the machinery involved in energy-producing chemical reactions (Figure 3).

the center of it. Small beads representing molecules are hovering near the proteins, showing higher concentration either outside of the membrane or inside of it. The transport proteins are therefore regulating concentrations of molecules inside the cell, by controlling the passage of molecules through pores." />

the center of it. Small beads representing molecules are hovering near the proteins, showing higher concentration either outside of the membrane or inside of it. The transport proteins are therefore regulating concentrations of molecules inside the cell, by controlling the passage of molecules through pores." />